How Bars Helped Shaping the LGBTQ+ movement

It took several decades to be where we are now and there is still a lot left to do. Pride month is just the tip of the historical iceberg when it comes to what the LGBTQ+ community has had to go through to achieve the recognition and respect it deserves.

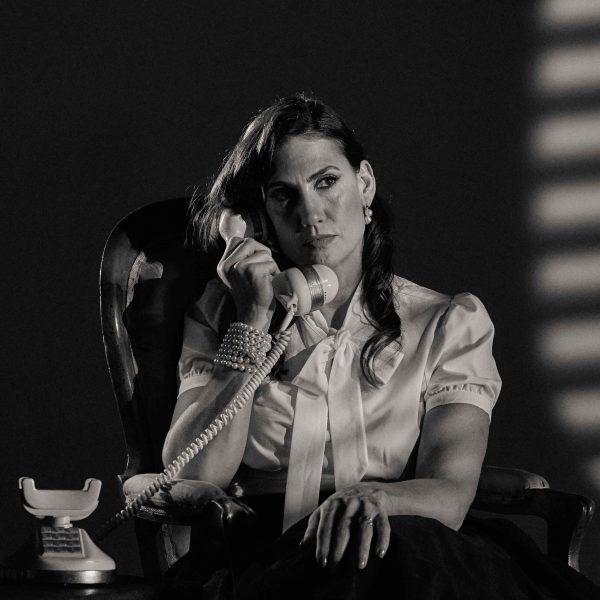

It all started outside of a bar. Professor Daniel Hurewitz, from New York Hunter College, took Campari Academy on a time travel through the major events in New York’s drinking culture that led to bars being a cornerstone in the gay movement’s evolution: “Bars operated like churches in other cultures for the LGBTQ+ community. Over time, the significance of the relation between freedom and hangouts evolved”.

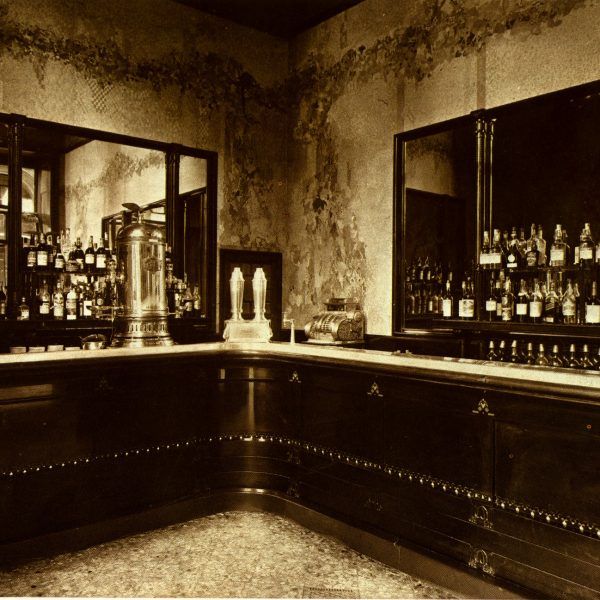

During the 19th century in the United States bars existed principally for men, fueling a bachelor subculture that dominated saloons and parlours. “The economic revolution allowed men to live alone, at least fifty percent of the male population in New York City was single. Saloons were their reward,” comments Hurewitz. Bars featured entertainment and cameraderie: drinking, playing cards, games, conversation. These places were the hubs where men found out about jobs, accomodation, politics: “Working class social life thrived in saloons, and its members proved their masculinity there, either winning at games, or buying drinks”. Occasionally, female charachters entered saloons: they were commercial sex workers.

Bars were actually hang out places where commercial intimate intercourse was offered regularly. Among the people available for men to have sex with there were the so called “fairies”: men dressed and behaving as women. Hurewitz adds, “Saloon patrons wouldn’t necessarily consider the gender of a partner for the night, as long as the person they were having sex with was idenitified as feminine. There were bars in the Lower East Side specifically designed to find fairies: they were well known figures in this period. They weren’t loved, but yet, accepted”.

Restaurant and club owners, sniffing out the opportunity, started promoting themselves as open to having gender nonconforming performers. Probably the most successful one at the time was Jean Malin: a son of immigrants, he had tried working on Broadway as a drag act, more or less failing, but in the early 1930s was invited to be the Master of Ceremonies in a speakeasy called Club Abbey. “The promoters saw that having a performer like that as the main attraction would draw a crowd. He wouldn’t appear as a female impersonator, but as a (so called then) “pantsy”, so recogninzed as gay. He would heckle and joke with guests, pretty much like drag queens nowadays. It was a show.” As Arthur Pollock of Brooklyn Daily Eagle worte in his column, “I don’t know what Jean Malin is, but he’s clever”. Malin, not even in his thirties, sadly died in a car accident a few years later, making it impossible for following generations to fully understand his impact.

But right when fairies and pantsies were part of the city’s social texture, things abruptedly changed. In 1933 the Volstead Act was officially overturned, marking the end of Prohibition. This led to new rules for the places that wanted to (re)open: in order for a bar to keep the license to sell alcohol, sexual amorality wouldn’t have been permitted. “Homosexuality specifically, was not allowed, otherwise the bar would shut down. A new phase started, where segregated night life was in action. Homosexuals were binded to specific illegal bars, ran by people who had lost jobs with the end of Prohibition. Arrests and raids were daily happenings, and queer nightlife became much more dangerous”.

Within these hidden locations, nevertheless, good times were lived, and a strong community was being born. “Everyone going to these bars was facing risks. So segregation brought people to understand that facing risks would allow them to meet other individuals that shared their same beliefs and identity. Solidarity and political mindfulness were nurtured in dedicated bars, and the whole homosexual community grew stronger: gays and lesbians were bonding, very often because they would count on each other and pretend to be straight couples if raids happened”.

The middle of the 1960s saw the very first public protest for gay liberation, focusing on LGBTQ+ members being allowed in public spaces. The energy, the awareness, the change happening, it all merged in 1969: “We can easily say, a bar is where the LGBTQ+ movement really came alive. Stonewall Inn, in Greenwich Village, was home to the now famous Stonewall Riots; the gay community found the courage and pride to stand tall against the law enforcement abuse they were suffering consistently, and right on the doorstep of this drinking parlour, a revolution began. The Riots are why Pride is celebrated every year, it’s the determinaton to have a recogninzed space in public, and to be separated maybe, but not used as a political instrument”.

Bars are the gathering places where any community is formed, and a sense of belonging is shaped. “The LGBTQ movement finds bars as points of reference, the heart of gay neighbourhoods. The stage from where it’s possible to claim what’s right: it was a desire to be left alone, at the beginning. Nowadays, it is a desire to be considered and appreciated”.