From Feasting Halls to Bars – A Journey Through Hospitality By Dave Broom

I’m looking at a pile of stones. There’s the line of a wall, people scraping in the dust with their trowels, intent on their work. This is the Ness of Brodgar on Orkney, a narrow isthmus between a loch and the sea, bookended by two stone circles. It is one of the largest collection of Neolithic buildings in Northern Europe, a place which was occupied for 60 generations from 3,500BC to 2,300BC. This particular pile, rejoicing in the romantic name ‘Structure 10’, was the feasting hall.

What has this to do with 21st century bartending? Everything. Structure 10 shows that the people of the Neolithic valued hospitality so highly that they had buildings dedicated to it. This was large hall, constructed from sandstone flags of different shades, decorated with pigments, with patterns etched into their surfaces. It is a grand statement, made by a people who had settled and established a community in this location, a culture which had hospitality at its heart.

For me, this shows how hospitality is hard-wired into our systems. It is there in Ancient Greece and Rome, it plays a central part in Icelandic sagas. All of these accounts speak of how people gather together and listen to poetry and music, how they eat and talk, their cups of wine or mead being filled and refilled by …staff. Why do we find variations on this theme in every culture? Because hospitality is a way of binding a community together, sharing food, sharing drink.

So important was this to a culture that in 7th Ireland, every householder was bound by the Brehon Laws to offer food and board to any traveller who arrived at their door. Whether enshrined in law or not, there is so much tied up within this to show that we as a species are naturally predisposed to offer hospitality.

By the Middle Ages, the feasting hall had been replaced by places dedicated to the taking of food and drink. In the UK we saw the emergence of low-class alehouses serving home-brewed beer, taverns where the better-off could indulge in vinous adventures, and inns which provided lodging and sustenance for travellers.

‘Come, sit, eat, drink, share your stories’. Every culture has its own variation on this theme. Though called by different names, the principle remained, that these are places to gather and meet, the hub at the heart of a community. What is the reason that in the UK they are known as public houses? Because they are the opposite of private. Rather, they are open to all, a welcoming space.

The ideas behind the American War of Independence were not formulated in grand drawing rooms, but in punch houses, democratic places where all were welcome, where ideas could be discussed, arguments made, a space for the exchange of ideas.

Today’s bars are equally democratic. It doesn’t matter who you are, or what your background is. You are (or should be) welcome. They are neutral paces where life and the world can be discussed – as well as places to relax and forget about the world!

In other words, nothing has changed, even if the emphasis has shifted from those early days of taverns and inns to today’s more specialised and diverse offerings. The reason why is because we are social animals who crave and enjoy company. A bar is the perfect place to indulge in this behaviour. That’s bar culture.

Of course there will be a difference in expectation between the bar in a 5-star hotel and a dive bar. The service will be different, as will the offering, the dress code, the decor – and the customer. Within this overarching concept of ‘bar culture’ there are also a multiplicity of cultures within bars. These could be dictated by theme – it could be tiki, whisky, or high-concept cocktails; by location – a beach or a city – which can then be extended to the way bars reflect as well as dictate the drinking culture of the country. Italy is different to Japan which is different as the US, is to Norway, France, or the UK.

These differences between cultures is one of the joys of bartending. Understanding the rules and manners, techniques and habits of the world’s bars is to explore the richness of being human and it is this which I am excited about exploring in the Academy.

Hospitality is universal, but bars shouldn’t feel that they need to compromise and dilute their offering to try and achieve mass appeal. Just as with music or film, customers’ individual tastes and preferences will dictate where they drink and feel the most comfortable.

The most extreme example of this is Tokyo’s bar district of Golden Gai, where each of its 270 bars, most of which can only seat a maximum of 10 people, has its own theme – it could be free jazz, punk rock, black & white movies, or hard-boiled fiction. Every cultural niche is covered here. You find where you best fit in.

And yet for all this diversity in bar types around the world, the same principles apply. The welcome, the question and the response, the delivery. Bartenders set the mood, they conduct. They are therapists, friends, confidants, but without imposing themselves. They control and yet they also serve. It’s a fascinating role.

The bartender is the conductor, the all-seeing eye stopping some things happening, and starting others. The space is for the guests, not a set for their ego to rampage through. It means that if you are pouring a beer or a glass of water that it is done with the same care as the most complex of cocktails. The customer wants a drink? You give them the best drink you can.

It comes back to understanding that democratic/neutral space. It means being able to read a room and people’s moods, and then responding in the right way. It is more than making drinks. It is about making everyone welcome, whether they want to sit quietly or have a fun time. It’s stopping thinking of them as customers and starting to see them as guests. That’s hospitality.

This is also what, I believe, underpins the Campari Academy. Other initiatives have looked at serves, at educating about brands and liquid, but no-one to my knowledge has stepped back in order to see this bigger and more complex picture. Maybe the fact that it is complex might be the reason for that.

Production is fascinating, as are ways in which drinks can be made, but by keeping the conversation at the level of brand the nature of hospitality is forgotten. How to use it in drinks is obviously valid, ways of moving the tradition forward is vital, but if we are to engage with bartending in a new way the discussion has to go so much deeper. The differences, the learnings, the shared stories and experiences, what can be taken and adapted. All have to be considered.

Community lies at the heart of this. Not just the communities which bars serve in their varied ways around the world, but the community within bartending. The manner in which the art of hospitality has evolved has come through sharing ideas, borrowing some, adapting others. That also is what the Campari Academy is about. This is an open space in which we can all discuss and learn – it’s a giant bar, it’s a feasting hall.

One of the driving forces behind the Academy is finding new ways to speak about bartending, community, and culture. It is about looking forward and not simply being tied to the past. The idea that, ‘it has always been done this way, therefore it cannot change’ results in a craft (and bartending is a craft) becoming ossified. There should be a conscious need to move things forward.

The counter-balance to that is that we can only do this by understanding and respecting the past and where we have come from. It might seem strange to go as far back as the Neolithic, but I think it’s important to understand that what we are doing 5,000 years later is part of who we are, that we are part of a continuum. The nature of the job has changed, bars and bartending has evolved, but the principles of hospitality are unchanged.

The Academy takes an holistic view of hospitality, the way in which we operate, the links which exist, the numerous facets of this cultural experience which starts when we all open that door to that bar, no matter where it is in the world.

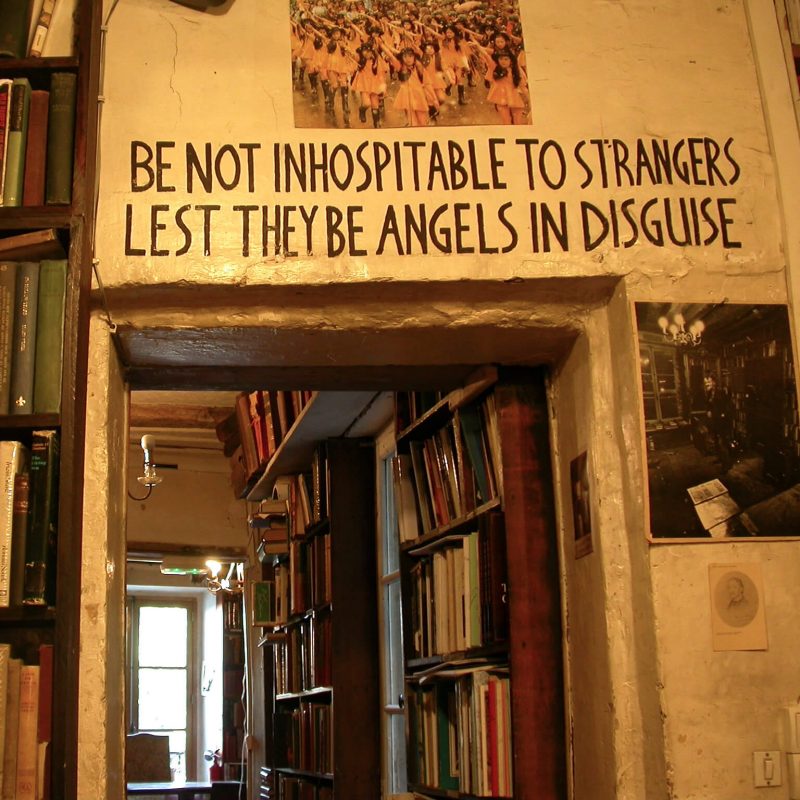

There’s a bookshop in Paris called Shakespeare & Company. On one of its walls its former owner George Whitman write ‘Be not inhospitable to strangers lest they be angels in disguise’. That impulse has existed in us for millennia. It sits at the heart of bartending, it sits at the heart of being human.