Scorpion Bowls and Survival: A Chinese-American Cocktail Legacy

How immigrant ingenuity—and a splash of rum—helped shape America’s tropical cocktail culture.

By Jason Doo

Jason Doo is a bar owner and lover of crab rangoons from Cambridge, Massachusetts. He is passionate about food history and is a dedicated collector of ceramic art.

Like any true Chinese restaurant, my childhood memories begin with picking vegetables after school, sitting at a table in the corner of the dining room. In the early ’90s, ours was a classic suburban Chinese-American spot on Main Street in Malden, Massachusetts—and like so many others, it was more than just a business; it was our family’s way of surviving after immigrating from China.

After the Chinese Exclusion Act and waves of anti-Asian sentiment, Chinese-American families had to get creative. Most other jobs were closed to us, and “authentic” Chinese food wasn’t exactly in demand with mainstream America. So families adapted. One way many did this was by opening restaurants—and with the help of a handful of Chinese restaurant distribution companies, they found a path forward.

Photo courtesy the author’s mother.

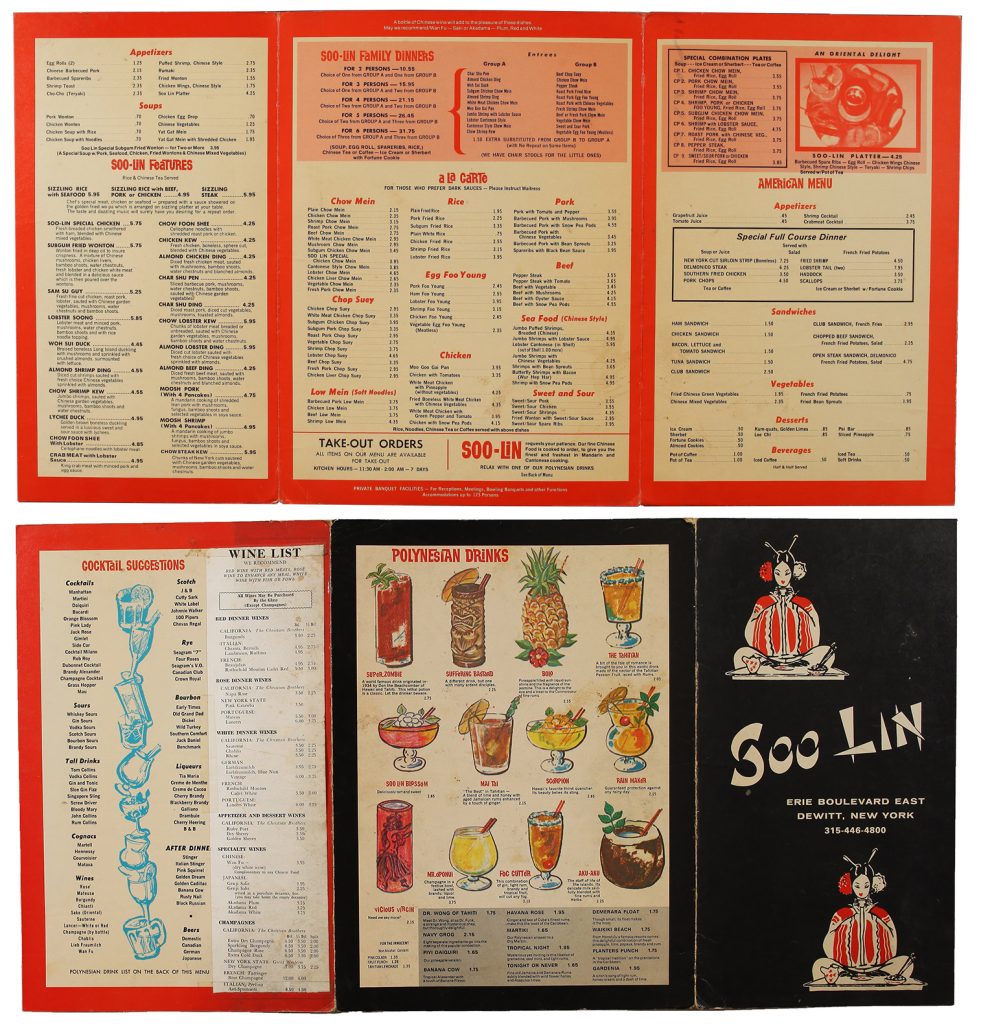

These companies didn’t just supply food and equipment—they offered roadmaps. They provided kitchen gear and menus pre-loaded with “American-friendly” Chinese dishes like General Tso’s Chicken and Beef & Broccoli, paired with elaborately illustrated cocktail sections featuring Zombies, Mai Tais, and Scorpion Bowls. The aesthetics leaned into the tropical: dragons, bamboo, and tiki idols often appeared side-by-side on laminated pages, with occasionally bizarre translations like “Cowboy Sauce.” With this template in hand, families could open quickly, serve what customers expected, and succeed.

The result was something remarkable: a loosely connected network of family-run Chinese-American restaurants that looked and felt strikingly similar from California to the Carolinas. Each one adapted its menu slightly to suit local tastes, but the foundation—sweet-and-savory Chinese dishes alongside kitschy tropical cocktails—remained the same. In a way, this became the largest unbranded restaurant chain in America, with no central authority—just a shared language of survival passed from family to family, menu to menu.

It was never explained to us why there were volcanoes on the menu, or why the bar had carved idols and paper umbrellas. Everyone else served Scorpion Bowls, so we did too. We used canned pineapple juice, bright red cherries, and sour mix, poured into painted dolomite pineapples or flaming volcano bowls dusted with cinnamon. We flipped through our “uncle’s” first edition Trader Vic’s cocktail book and followed the recipes, never really questioning where they came from. It wasn’t called tiki to us—it was just Chinese-American. I still have that book.

Looking back, it was more than a gimmick. It was a tactic for survival and assimilation. The tropical theme helped Chinese restaurants feel more “American” and trend-forward, especially to white, working-class suburban customers. It blended easily with existing Chinese décor—dragons, lanterns, bamboo—and leaned into the exoticism guests already expected. Most importantly, cocktails had far better margins than food.

Menu image courtesy the Harley Spiller Collection, University of Toronto Scarborough Library, Archives and Special Collections (Toronto, ON, Canada)

Tiki, for all its complicated and problematic history, offered something powerful: it allowed Chinese-American restaurants to stand out while fitting in. A mashup of Asian and Polynesian aesthetics made it feel familiar but unplaceable—an aesthetic no one could fully claim, and one that many immigrant restaurateurs used to their advantage.

When I reflect on my family’s restaurant and others like it, I see not just kitsch or nostalgia, but brilliance. This wasn’t cultural confusion—it was cultural strategy. A way to stake out space in a country that had tried to keep us out. A way to turn food and drink into belonging.

Today, many of these old-school Chinese-American restaurants are closing—not because they failed, but because they succeeded. Their children were able to go to college and pursue careers that didn’t require 12-hour days in a hot kitchen or charming guests behind the bar. These restaurants gave the next generation freedom. And with that, this particular branch of ‘tiki’—shaped by Chinese-American hands—will slowly fade. So enjoy another Mai Tai and crab rangoon while you can. It’s more than a cocktail and a ‘Peking Ravioli’—it’s a toast to the ingenuity, grit, and quiet victories of a generation.